אין לי ארץ אחרת

נולדתי בארץ בשנת 1953 להורים שורדי שואה, צילה ומאיר פרי ז"ל.

אמי נולדה בלושה, פרבר של העיר וילנה בפולין, היא נולדה למשפחה רבת אמצעים. בתקופת השואה, משפחתה נמלטה מהגטו ועברה לצד הפולני, הם הצטיידו במסמכים מזויפים וכך, בפחד יום יומי מחשש שיתגלו הצליחה רוב משפחתה לשרוד. אביה ישראל, ואחיה יהושע הי"ד נרצחו עוד בהיותם בגטו בסלקציה שהתחוללה בגטו ולא זכו להיקבר. אחת מאחיותיה, בתיה, שאני נושאת את שמה נפטרה ממחלה קשה בגטו. בני המשפחה ששרדו: סבתי בוניה, דודתי גסיה ודודיי יצחק ויהודה.

משפחתו של אבי, מאיר, חיה בעיר ביאליסטוק ברוסיה. במשפחה היו שלושה בנים ושתי בנות: אבי מאיר, אחיו דב ונחמיה ואחיותיו חנה ודינה. אבי היה חיל בצבא הרוסי וכך שרד. לאחר המלחמה חזר לביתו וגילה שלא נותר שריד ממשפחתו והוא היחיד שניצל. מקומיים הזהירו את אבי לעזוב את המקום במהרה, שכן חייו בסכנה מצד התושבים שבזזו את רכוש המשפחה. אבי החליט שמקומו רק בארץ ישראל. הוא שהה במחנות מעבר לארץ שהיו בגרמניה, הוריי הגיעו לשם בנפרד ושהו שם 4 שנים. הוריי הכירו שם זה את זו ונישאו, אמי הרתה ואחותי נולדה במחנה מעבר בעיר פוקינג בגרמניה.

כל עת הייתה אהבה גדולה במשפחה גם בתקופות הקשות והאכזריות ביותר ברעב, בסכנה בדרך-האהבה תמיד ניצחה! הוריי עלו לארץ ב1949 עם תינוקת בת 8 חודשים והועברו לגור באוהל במעברה בבית ליד. אבי, כדי לפרנס את המשפחה, עבד במפעל אריגה ברמת גן.

אמי צילה, אחיה יהודה ואמם הקשישה, חיו באוהל בתנאים קשים מאוד בבוץ, בקור ובמקום שורץ עכברים. אבי בחריצותו הרבה הצליח להעביר את המשפחה לבתי עולים ברמת גן. אמי סיפרה בהתרגשות לאחר שנים, שבבית החדש שבו היה חדר אחד, היו מים זורמים בברז, שירותים ומטבח. לאחר ארבע שנים נולדתי, בהיותי בת שנתיים עברנו לדירה מפוארת במושגים של שנת 1955: דירת 3 חדרים במרכז רמת גן. אני זוכרת בערגה את תקופת הילדות. כולם חיו בצנעה, לא היה טלפון, לא טלוויזיה, לא מכונית. האזנו לרדיו הרבינו לקרוא ולהחליף ספרים בספריה. כל השכונה שיחקה בחוץ על הדשא משחקי רחוב ובבית משחקי קופסא. רק למשפחה אחת ברחוב הייתה מכונית ולקחו אותנו הילדים מידי פעם לסיבוב בשכונה. היה לנו בית שמח. נכון שהוריי ניצולי השואה האזינו בקנאות לרדיו ל"מדור לחיפוש קרובים" בתקווה למצוא קרובי משפחה שנעלמו בשואה. כמו כן הקשבנו כולנו למשפט אייכמן. אבל אפשרו לנו לטייל בארץ, לצאת עם חברים חינכו אותנו לעצמאות. ערך אהבת הארץ וערך הלימוד וההשכלה היו חשובים ביותר להורי. אחותי ואני היינו תלמידות טובות וזה הקל על הורי. לא היו גאים ונרגשים מהם כשהתגייסנו לצבא והגענו עם מדי צהל. כמה היו גאים בהישגינו האקדמיים שלנו. בעיני הורי היינו הבנות המוצלחות ביותר והיפות ביותר כשהתחתנו,

לבעלים שלנו לא היו מתחרים ועל הנכדים בכלל אין מה לדבר – מושלמים! הם הרעיפו עלינו אהבה ומסירות אין סופיים. אבי, לצערי, לא זכה לחוג את נישואי ילדיי. אמי זכתה להשתתף בחתונות של שתי בנותיי אפרת ומיכל וזכתה לראות שני נינים ברק ונועם. צרוב בי זיכרון עמוק להתרגשות אבי בחגים. עד נישואינו הסבנו לשולחן החג ארבעה: הוריי, אחותי ואני. לאחר הנישואין המשפחה גדלה נוספו הבעלים והנכדים זו הייתה תשובתו לשואה ולאבדן משפחתו. אבי הקשוח התרגש עד דמעות.

סיפור מותו של אבי היה טרגי מאוד למשפחתנו. אבי נהרג בשבת בצאתו מבית הכנסת בדרכו הביתה. הוא נהרג בתאונת פגע וברח, לעיני כל המתפללים על מעבר החצייה, כשהוא עוזר לאדם צעיר ממנו לחצות את הכביש. אבי נהרג במקום והאדם שאבי עזר לו ניצל. אבי נפטר כפי שהוא חי תוך עזרה לזולת.

ביום חמישי האחרון בחייו יצאנו אבי ובני נדב, שהתעניין מאוד בנושא השואה לסיור ב"יד ושם", נדב היה בן 11. התמונות שילוו אותי כל חיי הן של אבי צועד יד ביד עם נדב תוך הסברים על המקומות והאירועים, זה היה ביקור מרגש מאוד. בסיומו הצעתי לאבי שנבקר בבקעת הקהילות, אבי לא היה שם בעבר. הסברתי לו שהאתר בנוי כקבר, כמפת אירופה ובהתאם למפה מצויות אנדרטאות עם שמות הערים והעיירות על פי מיקומן הגאוגרפי במפה, היו עיירות שנמחקו לחלוטין בשואה. אבי הסתקרן אם מצוינת העיירה של אמו, שהיו בה מספר בתים בלבד, אמרתי לו שאם היו ניצולים מעיירה זו נמצא אותה וכך היה, חיפשנו ומצאנו התרגשותו הייתה רבה היה לנו יום מסעיר וחווייתי. חזרנו הביתה מירושלים נרגשים מאוד. ביום שישי הגענו כולנו לבית הורי לארוחת השבת לא העלינו בדעתנו שזו תהיה ארוחת הפרידה מאבי. המשפחה נוכחה בשלמותה. אבי היה המאושר באדם להיות מוקף במשפחתו שכל כך אהב. בשבת נפלו עלינו השמיים. זכרו של אבי מלווה אותי תמיד, בכל מעשיי, בכל החלטה, תמיד חושבת מה היה אומר וכמה נחת היו מסבים לו נכדיו וניניו. הערכים שהורי נטעו בנו: אהבת הארץ, עזרה לזולת, ראיית האדם הפכו להיות חלק מהווייתנו. אותם ננסה להעביר הלאה לדורות הבאים.

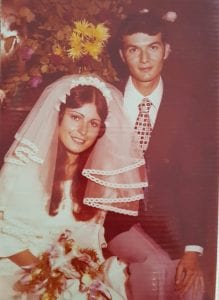

את בעלי דני הכרתי במהלך שירותינו הצבאי. כאשר הייתי בת 18, פקידה פלוגתית בחטיבת שריון ודני היה מפקד טנק.במהלך תקופה זו התרחשה מלחמת יום הכיפורים. לאחר המלחמה התחלנו ללמוד באוניברסיטה והתחתנו בסיום שנת הלימודים הראשונה. תקופת המלחמה הייתה מאוד טראומטית כיוון שדני לחם בחטיבה של אריק שרון שצלחה את תעלת סואץ ואיבדנו חברים רבים.

לאחר המלחמה חזרנו ללימודים והתחלנו את חיינו כמשפחה

נולדו לנו שלושה ילדים: אפרת הבכורה, מיכל ונדב. היום אנחנו סבא וסבתא לחמישה נכדים.

לאחר לימודי האקדמיים לימדתי ספרות במשך שלושים וחמש שנה בתיכון עירוני י"ד בתל אביב. עסקתי בחינוך וב-13 השנים האחרונות ניהלתי את החטיבה. היום אני גמלאית, מתנדבת, לומדת, מטיילת, עושה פעילות גופנית ונהנית מהחיים.

להלן תיעוד סיפורה של אמי, צילה ז״ל, מהקורות אותה ומשפחתה בזמן מלחה״ע השנייה:

לזכר המשפחה

Tsila Peri wartime memoirs (1)

The Diaspora Museum

Tel Aviv, Israel

Year Study Course

20.6.1995 Work submitted by Stephen Schulman to Rifka Aderet

An account of wartime experiences in Poland under Nazi Occupation

As recounted by Tsila Peri

DEDICATION

This short work is dedicated with deep affection and respect to my mother in law Tsila Peri (nee' Bastomski) and to the memory of her beloved father Israel and her brother Joshua so cruelly murdered by the Nazis.

FOREWORD June 1995

This story that follows is a true account of the wartime experiences of my mother in law Tsila Peri (nee' Bastomski) now living in Ramat Gan, Israel as related by her to me.

Tsila is a good, quiet, modest and unassuming person who is not in the habit of talking about herself. In all the years that I have known her, she has sporadically talked about her past, mentioning experiences here and there. However, she has never sat down to systematically retell all. With the passing of time, I felt that it would not only a good idea but a "mitzvah" to put down in writing and record for posterity, the ordeals she and her family went through. Tsila was kind enough to sit down and tell them to me – an act greatly appreciated.

״I came on aliya from South Africa a country with a predominantly Lithuanian Jewish community which arrived mainly in the early 20th century. My grandparents, like many others, had immigrated there circa 1900. Thus, luckily, as all our immediate and extended family was with us, we did not feel the Holocaust directly. In the course of time, I had read about it and acquired a reasonable knowledge. The vast store of facts and figures, however, tended to numb and the immense scale of horrors and atrocities to lose some of their meaning and human dimensions.

On coming to Israel, I began to feel directly for the first time its full extent. It is awesome and absolutely incredible that so many people actually went through so much, endured so great an amount of suffering and retain their innate dignity, sanity and humanity. I am constantly awed and humbled.

What brought this home to me was my coming into contact with many Holocaust survivors. Only when sitting down face to face with someone who has gone through it all and actually hearing their account, do the stories acquire a human dimension and so genuinely enable the listener to relate to them directly. Through Tsila and my father in law Meir (himself, the only survivor of his immediate family) was I able to hear them at first hand. It was an edifying experience and I am very grateful to them for having done so. It wasn't easy, as recounting them evoked many painful memories. I am sure that doing so, serves as a modest memorial to the memories of Israel her father and Joshua her eldest brother.

An Account of My Wartime Experiences in Poland under Nazi Occupation

As recounted by Tsila Peri (nee' Bastomski) to Stephen Schulman during the months of May and June 1995

A Brief Background and Autobiography

My family lived in a settlement called Kolonia Losza which situated about 40 km. from Vilna on the main road that led to it. Our house was approximately 1 km. from the village of Losza which contained a few hundred inhabitants, all of whom were Polish peasants,

The house itself stood alone and was surrounded by lands that we had bought from the local nobleman. Our family was very well off. One of our sources of income was a family factory that produced turpentine and axle grease for the wheels of wagons. These substances were produced from tree stumps and roots which either had grown on our land or were bought from the peasants (they were paid per cubic meter) in the surrounding areas. The factory stood near a wood that also belonged to our family. In the factory, the wood was burned, liquid extracted from it and then with the help of centrifuges, the turpentine was separated from the axle grease and both were stored in barrels. These, in turn, were transported by wagon to the railway station of the small town of Gudegai located 4 km. away. There was even a watchman called Sokolowski with the large dog to look after the large stockpiles of wood.

Our house was large and our lands extensive. We grew our own vegetables and in addition had a general store which sold just about everything and anything to the population of the neighboring village – from headache pills for the local nobles down to chocolates and even harnesses for horses. There was a large underground storage facility kept cool with ice. In it were stored meat and drinks. These too, were sold to the local populace.

I am the youngest in the family and was born when my parents were quite advanced in age – a "bat zekonim". The eldest in the family was a sister called Batya born circa 1906 who died in her late twenties. After her came my late brother Joshua born two years later. Gesia followed after a similar interval. Yitschak arrived in 1914, Yehuda four years later and I in 1925.

My late brother Joshua (Yehoshua) was a born merchant. He travelled the countryside, doing trade not only in wood but also in animal hides and other merchandise. He was a gifted person and a natural trader who even bought agricultural produce from the peasants. During the summer, when the local noble used his dacha as a "pension" for paying guests from the city, he supplied him with all the necessary provisions. Joshua was on very good terms with the local priest. In fact, the latter liked him so much that when our family was imprisoned in the ghetto, he sent someone to offer to get us out and save us.

The Beginning of the War Years

When the war broke out, all members of the family returned home. In 1939 when the Germans occupied Poland, one of the neighbouring nobles with whom we were on very good terms and who felt that he had to extend his patronage and protection to us, made an offer. He said that we were in danger as our house was situated on a road on which the Germans continually passed. He felt, therefore, it would be in the interests of our safety to close up our home and come and live on his estate. This we did and left two Poles who were in our employ to look after the house. One was a man and the other was a woman who lived in a room in our house and worked as a domestic. So, we moved with our belongings on a two horse cart to the noble's large home where we occupied a few rooms. Nevertheless, after a relatively short stay, we realised that this was not a viable long term arrangement and we returned home to Kolonia Losza. The road was relatively quiet and if any Germans were in the vicinity, our Polish employee would warn us in advance.

The Gudegai Ghetto

Soon after our return home, we were rounded up with rest of the Jews in the area and sent to the ghetto in Gudegai. There, we stayed with another family in very crowded conditions. I still remember the day of our departure. The Germans ably assisted by the local police came to collect us. People flocked from the surrounding areas to watch the show and crowded into our home like birds of prey. I gave them some possessions and after we left, they looted and took everything that they could carry.

I don't remember exactly how long I was in the ghetto, but I do recollect that conditions were very hard. Gesia worked for the railways and cooked for the dining room of the German managerial staff. I helped her and also washed and ironed their uniforms. It was hard work but bearable. The German civilian workers treated us reasonably.

Naturally, we were subject to the same inhumane rules and restrictions as imposed on the rest of the Jews under Nazi rule. The yellow patch had to be worn and we were forbidden to leave the ghetto. My late father disobeyed this rule and used to slip out regularly, dressed as a Pole without the yellow star, at the risk of his life to travel to our former home to get extra and vital food supplies for us. One day, he was caught and brought back to the ghetto to be publicly executed. All the populace of the ghetto was forcibly assembled and we were made to be in the center to watch the horrible proceedings. My poor father was hung before our eyes and denied even the decency of a Jewish burial – his body was thrown into a hole dug at the rubbish heap.

My dear brother Joshua was no longer alive. He had been conscripted into the Polish army and was at an air force base when the Germans overran it. We later learnt that they had looked for Jews amongst the soldiers. On discovering his identity, they murdered him.

The Flight from the Ghetto to Honchary

That the rest of us are alive today is only due to my brother Yitzchak. Risking his life, time and time again, he slipped out of the ghetto at night to arrange our escape. He first went to a Polish family friend who lived in a small town called Ostovetsk about 2km. from Gudegai. This man was the mayor of the town and the surrounding area which also included Gudegai within its jurisdiction.

A very interesting story lies behind this personage. He was a former school teacher who had quarreled so bitterly with a colleague that he had shot and killed him. While he was sitting in prison and his wife and children were in difficult circumstances, our family had given them food and provisions enabling them to survive. As a result, he felt himself in our debt and so when Yitzchak called upon him for help, obliged him.

It was hard for Yitzchak to reach this man. His sons were very anti-Semitic and he had fierce dogs to guard his home. Somehow, my brother got past them. Once contacted and in return for payment, he arranged for documents under Polish names to be forged for the entire family. Yitzchak also bought a horse and sled and travelled the countryside looking for a place of refuge for all of us. Finally, he came to the farm of a prosperous farmer living near a small village about 100km. from Vilna and there was informed that there was a small empty house in the woods near the village. A story was prefabricated and accepted that we were Polish peasants living in Vilna under Lithuanian rule. The Lithuanians were very anti – Polish and were making our lives a misery. We wished to return to Polish territory to live amongst our own. The same story was repeated to the head of the village and the forged documents were presented. We were then given permission to live in the small house.

In due time, Yitzchak returned to the ghetto and arranged our escape. In the dead of a cold, snowy winter night, all our remaining family slipped out from under the fence into the waiting sled and fled from the ghetto and certain death. Yitzchak had even obtained documents for two other people. Unfortunately, nobody outside our family wanted to take up the offer. Friends and acquaintances were fearful for us, warned us about the terrible consequences and advised us to stay amongst our own. They were little aware of the horrendous fate that was awaiting them. Indeed, the Germans had been so successful in spreading disinformation that the Jews in the ghetto thought they were going to Estonia to be resettled!

We spent the first night outside the ghetto at the home of the peasant where Yitzchak had stabled the horse. It was a fearful period for all of us. By the first light of dawn, we set out on our journey to the simple dwelling that was to be our home for the duration of the war. On the way, we stopped at the house of the rich farmer near our destination in order to sleep a little and feed the horse. We were so exhausted that when Gesia awoke, she noticed that her diamond ring had been stolen from her finger. She didn't say anything as we were certainly in no position to investigate the theft and in so doing, draw attention to ourselves.

The years in Honchary

At last, we reached the house near the village of Honchary – situated about 10km. from the town of Traby. The house was simple in the extreme with one or two rooms, an earth floor, a stove and a few miserable sticks of furniture. Running water, indoor toilet and electricity were unheard of luxuries! Of course, we had our fictitious stories that all the villagers accepted. It should be remembered that we had spent all our lives in the country amongst the peasants and so were familiar with their mentality, habits and customs. Our Polish was accent free and so this very sharp transition and complete change of identity was relatively mild. The new family name was Vitkowski. I was Helena, Gesia – Maria. Yehuda became Vladek and Yitzchak was Stanislaw. My mother's new name was Alexandra.

As for making a living, we managed in our own way. My two brothers found employment doing agricultural work in the fields of the local noble. Gesia found work as a seamstress in the local village as we had managed to bring a sewing machine with us. I assisted her with her work. There was a cow and needless to say, a pig – something every self respecting Polish peasant had in his yard!

Words cannot convey all the intense emotions we felt and all the experiences we underwent during this trying time. We lived in constant fear and dread of being found out. To all extent and purposes we were Catholics and behaved like them. There was a crucifix on the wall of our house and we all wore them around our necks. We were devout and attended church regularly. We went there every Sunday with the villagers and crossed ourselves in public as the occasion demanded and the need arose. Like all the simple villagers, we walked there barefoot with our shoes in our hands and only put them on before entering the church.

Our family knew the village priest. I spent some time at his house doing some sewing and household work. He was kind and polite man who had a very pretty housekeeper. Yehuda had a respected task in the service of Jesus. Whenever a villager died, his job was to put on a white smock, obtain the cross on a pole from the village priest then walk at the head of the funeral procession holding it in front of him. If the Polish peasant who lay so peacefully in his coffin had known that a Jew was leading him to his place of eternal rest, he would have spun very rapidly in his grave!

We observed all the holy days of the year. We even went down on our knees to pray at night when we had company. Before Christmas we all went to the confessional. In the month of May, people were more devout. Accordingly, like others, every time we passed a roadside shrine we would get down on our knees and pray.

In spite of all this outward show of religious fervor, I am sure that some people suspected us. After all, a Pole has a sixth sense for Jews. Nevertheless, we managed to survive. We were very useful to the people of the village: Gesia with her sewing and Yehuda the unofficial village barber. A man from the village befriended us and often came to visit. One day, he entered our home his face shining with happiness and mentioned that he had something heartwarming to tell us. It appears that he had been in the town of Molodetsna some 30 km. away. There, this good soul had seen the Germans herd the local Jewish populace into a pit that that they had been previously forced to dig and then shoot them. Not everyone had died immediately. All the bodies formed a low mound after they had been covered with earth. We were forced to listen and pretend that we shared his happiness.

One unforgettable period was my mother's illness. She had become very ill with jaundice and was delirious. In this state, with death so near, we had no choice as was the custom, but to summon the village priest for confession. Mother was babbling in Yiddish from time to time – completely unaware of and with no control over what she was saying. The priest came, went into the room, spent some time there in the privacy of the confessional and left. Some Higher Force was watching over us for my mother's lips were sealed and she never gave away our identity.

Life was one of constant tension. Night gave us no relief. Only when the weather was extremely inclement with heavy rain or thunder, did I feel any degree of safety. In the woods around us were partisans. There were two main groups. One of them was extremely nationalistic, highly anti – Semitic and spent part of its time searching for Jews to exterminate. There was a hunchback shoemaker in the village that was on friendly terms with us and often ostensibly dropped in for a visit, but we suspect, really to snoop around. He might have informed them of his thoughts concerning us, for one day they appeared out of the woods, started to interrogate us and check our documents. Apparently, they weren't satisfied with our explanation and so the band set out to look for my two brothers who were working in the fields. On seeing them from afar, Yitzchak took to the woods and hid. Yehuda wasn't so lucky. They demanded the ultimate proof of his identity. Just as they were about to make him drop his pants, their officer gave them an order to cancel their action. Once again, by a miracle, the family was saved. I suspect that the officer was really a Jew, but this is only speculation.

The peasants of the village were naturally suspicious people and at one stage, word reached our ears that the inhabitants of Honchary were talking about us. This problem was temporarily solved when we all moved in with a young woman who lived near us. We regularly used to fetch water from her well and so got to know her. Her husband being away at war, she was alone with two young children and fields to look after. My mother suggested to her that we come and stay in her home. It would help cure her loneliness and insecurity. Moreover, my brothers would tend her fields. The suggestion was duly accepted and the new situation was one of mutual benefit. Let it not be understood that the new home was luxurious, being more or less the same as the previous one. Still, being with her gave us a stronger standing in the community. Furthermore, her word carried weight in the village and she could testify to our devoutness during evening prayers.

The German army was in the vicinity too. Fortunately, we had very little contact with them. Our house was situated in the woods, off the main road and could only be reached by travelling down a dirt path. When they came down the road to Traby to buy provisions, they always used to shoot in all directions with the intent of warding off any possible attacks by partisans. Whenever we heard the shots, we were terribly frightened as we always thought that someone was coming to take us away. The Germans came to our house a few times – only to enquire about food and not check our documents.

Life had its lighter moments too. Every Sunday there was a dance in the village. The young people came to see and be seen and dance to the music of a violin and a badly played accordion!

I was then a young woman and had friends among the village girls of my age. It was very hard because on one hand, we were young and had to have a normal social life. There was a young man in the village that showed an interest in me. Some village girls had their eyes on my brothers. On the other hand, caution was the word and we had to keep ourselves apart. Like my contemporaries, I learnt the skills of the village, one of which was producing cotton thread. We young girls would assemble together at someone's house, take the raw, dirty cotton, separate it from the bolls and then in a long arduous manual process, spin it into threads. We did this many times and sometimes a whole night would be spent doing it. I even used to spin thread for the woman that we stayed with.

The War's End and Our Departure from Honchary

Finally, the war's end arrived. It wasn't very dramatic. There was no radio in Honchary but newspapers did reach us so everyone expected the end to be in sight. One evening on the road leading past the woods we heard voices in Russian. We were very frightened and as we women were alone, out of fear we hid in the woods. Emulating the locals, our clothes were buried for safety in the ground. A decision was reached not to prolong our stay and leave as soon as possible. The villagers were told that since Vilna was no longer under Lithuanian control, our desire was to return to it without further delay. We bid farewells and travelled by cart with our meager belongings to Hoshmiana, a large city 100km. from Vilna. Finally, we retraced our steps to Gudegai, having been careful not to reveal our destination to our former neighbours.

There was no point in returning to our house and lands in Kolonia Losza. We had checked and seen that what was portable had been looted and carried away and that the house was completely destroyed. Gudegai was known territory and in it, the few Jewish survivors were fearful and preferred to be together. After all, sometimes, safety lay in numbers. A house was rented, my brothers found work and I was a clerk in a post office of Ostrovesk, a small town nearby. Gesia left for Vilna. She then married and moved even further away to Tashkent in Uzbekistan. In time, I progressed in my job and attained a position of responsibility.

The Move to Bialystok – Poking – Israel

With the passing of time, all the Jews began talking about leaving Byelorussia and moving to Poland. The political climate wasn't good and there was great uncertainty about the future. We made application to leave and this was granted. We left by train via Warsaw to Bialystok. A cow which was in our possession went with us. It was of great value and couldn't be left behind.

In Bialystok, urban kibbutzim had been set up by various Jewish Zionist organizations such as Hashomer Hatsair and Mizrachi. There was an air of anti – Semitism in the city and living within these groups gave a feeling of security. Their emissaries were hard at work persuading us to join them. Eventually, we went to the Dror kibbutz. From there, the kibbutz moved to a huge Displaced Persons camp in Poking, Germany where we remained for a number of years. I learnt sewing and seamstress work, studied instruction at Munich and became a teacher in an ORT school. There, in the camp, I met Meir and we married in 1947. My elder daughter Yona was born a year later whilst we were still in Poking. After waiting our turn, we came to Israel in 1949.

Gesia remained in Tashkent and was widowed during the post war Stalinist purges. She managed to leave the USSR in 1956 to join us here. Yitzchak moved to Los Angeles. Yehuda stayed in Israel for some years and then joined Yitzchak. My mother, Bunya stayed with us for a period of time before moving to Los Angeles where she, in time, passed away.

Postscript 2nd April 2010

It is with great sadness that I write this, as our dear Tsila passed away yesterday, on 1st April 2010. This brings the Bastomski family Kolonia Losza saga to a close as Gesia, Yehuda and Yitzchak had all preceded her. Nevertheless, the forces of goodness have triumphed and prevailed over the evils of Nazi Germany and all their accursed collaborators. Tsila, her sister and brothers have left behind children, grandchildren and great grandchildren who shall always remember them with love.

Post- postscript 17th October 2014

This year we commemorated our dear Tsila’s fourth yartzeit and the yartzeit of our dear Meir who had passed away under tragic circumstances thirteen years previously. Meir had been conscripted into the Polish army prior to the war and as the Red army advanced into Poland, it then incorporated the Polish one. He was on the front, wounded and served as a medical orderly on a hospital train. After the war, he returned to his native Bialystok to discover that his parents, brothers, sisters and their families had been murdered in the Holocaust and that Poles, having taken possession of his family home and all their possessions were less than pleased to see him. He valued his life, took the hint and quickly departed that accursed town never to return. Meir never expressed the desire to visit. He used to say, “What have I got to do there?”

Meir was tragically killed in a hit and run accident while crossing the road on a pedestrian crossing on his way home from Shabbat morning shul. The driver was never located. May his name be forever obliterated!

Tsila and Meir’s memories are blessed and both of them live on in the hearts of their children, grandchildren and great grandchildren.

Blessed Be Their Memories!

– Lest We Forget.

It should never be forgotten that the German army and the Nazi killing machine were aided and abetted by the local inhabitants and institutions of the countries they invaded and occupied. In many cases, they carried out their murderous work most diligently and ferociously without need or encouragement from their foreign masters. All these cases have been well documented.

Virulent anti – Semitism was never far below the surface and was often given vent in post war Europe. In 1946, a notorious pogrom in Kielce, Poland resulted in the murder of 42 Jews by the local populace, police and soldiers. There were many other incidents in Europe that reminded the few survivors that they were no longer welcome in the country of their birth. It is recorded that Poles, may their names be obliterated, in the post war period, murdered approximately two thousand Jews individually and in pogroms. Accordingly, it is very clear why the Displaced Persons camps were filled with so many Holocaust refugees.

הזוית האישית

סבתא בתיה: תכנית "הקשר הרב דורי" איפשר זמן איכות שלי ושל נכדי ברק. בזמן זה העלינו את סיפור המשפחה, פרטים רבים נוספו לברק בדקנו וראינו תמונות השווינו בין פעם להיום, העמקנו את הקשר בינינו!

הנכד ברק: אני חושב שהתכנית הוסיפה לי ידע חדש שלא ידעתי על סבתא, מאוד נהניתי ללמוד עליה ובסה"כ בילינו זמן איכות מאוד מיוחד!

מילון

יד ושםמוסד רשמי להנצחת זכר השואה בישראל הממוקם מעל הר הזיכרון בירושלים, בחלקו המערבי של הר הרצל. (ויקיפדיה)

המדור לחיפוש קרובים

המדור לחיפוש קרובים ולריכוז מענים של הסוכנות היהודית פעל בין השנים 1945 ו-2002, ונועד לסייע לניצולי השואה לאתר קרובים ומכרים שאבדו בזוועות השואה. (ויקיפדיה)

פוגרום קְיֶילְצֶה

פוגרום שאירע בשרידי יהודי פולין ב-4 ביולי 1946 בעיר קיילצה (Kielce) שבפולין, לאחר שנפוצה בעיר עלילת דם נגד יהודים שכביכול השתמשו בדם ילד נוצרי לצורך טקס דתי. בפוגרום נרצחו 42 מתוך 163 היהודים ניצולי השואה ששהו בעיר, וכ-80 נפצעו. (ויקיפדיה)

ציטוטים

”גם בתקופות הקשות והאכזריות ביותר ברעב, בסכנה בדרך, האהבה תמיד ניצחה!“